Port Chicago Incident |

by Shockd |

|

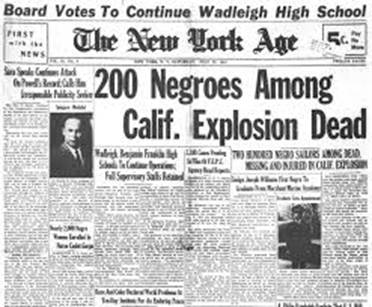

In 1944, the Port Chicago disaster killed hundreds of Black-Americans in a single blast. Was it an accident, or was it America's first atomic weapons test?

On the night of 17th July 1944, two transport vessels loading ammunition at the Port Chicago (California) naval base on the Sacramento River were suddenly engulfed in a gigantic explosion. The incredible blast wrecked the naval base and heavily damaged the small town of Port Chicago, located 1.5 miles away. Some 320 African-American naval personnel were killed instantly. The two ships and the large loading pier were totally annihilated. Several hundred people were injured, and millions of dollars in property damage was caused by the huge blast. Windows were shattered in towns 20 miles away, and the glare of the explosion could be seen in San Francisco, some 35 miles away. It was the worst home-front disaster of World War II. Officially, the world's first atomic test explosion occurred on 16th July1945 at Alamogordo, New Mexico; but the Port Chicago blast may well have been the world's first atomic detonation, whether accidental or not.

The Ships

The E. A. Bryan, the ship which exploded at Port Chicago, was a 7,212-ton EC-2 Liberty ship commanded by Captain John L. M. Hendricks of San Pedro, California, and operated by Oliver J. Olson & Co., San Francisco. It was built and launched at the Kaiser Steel shipyard in Richmond, California, in March 1944. She made a maiden voyage to the South Pacific and then was ordered into the US Navy's Alameda Shipyards where the five-ton (10,000-pound maximum load) booms and gear on the no. 1 and no. 5 holds were removed and replaced with 10-ton booms and gear. It then docked at Port Chicago on 13th July 1944. At 8:00 a.m. on 14th July, naval personnel began loading ammunition.

The E. A. Bryan had been moored at Port Chicago for four days, taking on ammunition and explosives night and day. Some 98 men of Division Three were hard at work loading the Bryan, and by 10:00 p.m. on 17th July the ship was loaded with some 4,600 tons of munitions including 1,780 tons of high explosives.

The Quinalt Victory, the second ship, was brand new; it was preparing for its maiden voyage. The Quinalt Victory had moored at Port Chicago at about 6:00 p.m. on the evening of 17th July. Some 102 men of the Sixth Division, many of whom had only recently arrived at Port Chicago, were busy rigging the ship in preparation for loading of ammunition which was due to begin by midnight. In addition to the enlisted men present, there were nine Navy officers, 67 members of the crews of the two ships along with an Armed Guard detail of 29 men, five crew members of a Coast Guard fire barge, a Marine sentry and a number of civilian employees. The pier was congested with men, equipment, a locomotive, 16 railroad boxcars, and about 430 tons of bombs and projectiles waiting to be loaded.

Most of the enlisted men, upon first arriving at Port Chicago, were quite fearful of the explosives they were expected to handle. But, over time, many of the men simply accommodated themselves to the work situation by discounting the risk of an explosion. Most men readily accepted the officers' assurances that the bombs could not explode because they had no detonators The Explosion Just before 10:20 p.m., a massive explosion occurred at the pier. To some observers it appeared that two explosions, only a few seconds apart, occurred: a first and smaller blast was felt; this was followed quickly by a cataclysmic explosion as the E. A. Bryan went off like one gigantic bomb, sending a column of fire and smoke more than 12,000 feet into the night sky. Everyone on the pier and aboard the two ships was killed instantly, some 320 men, 200 of who were black enlisted men. Very few intact bodies were recovered. Another 390 military and civilian personnel were injured, including 226 black enlisted men. This single, stunning disaster accounted for almost one-fifth of all black naval casualties during the whole of World War II. Property damage, military and civilian, was estimated at more than US $12 million.

The E. A. Bryan was literally blown into pieces. Very little of its wreckage was ever found. The Quinalt Victory was lifted clear out of the water by the blast, turned around and broken into pieces. The largest piece of the Quinalt Victory which remained after the explosion was a 65-foot section of the keel, its propeller attached, which protruded from the bay at low tide, 1,000 feet from its original position There was at least one 12-ton diesel locomotive operating on the pier at the time of the explosion. Not a single piece of the locomotive car was ever identified: the locomotive simply vanished. In the river stream, several small boats half a mile distant from the pier reported being hit by a 30-foot wall of water.

In a later interview, one of the men described his experience of the disaster:

I was reading a letter from home. Suddenly there were two explosions. The first one knocked me clean off... I found myself flying toward the wall. I just threw up my hands like this, then, I hit the wall. Then the next one came right behind that. Phoom! Knocked me back on the other side. Men were screaming, the lights went out and glass was flying all over the place. I got out to the door. It seemed as if the whole building was turned around, caving in. So we jumped in one of the trucks to go down to see if we could help.' We got halfway down there and the truck stopped?' The driver says, “Can't go no further.” There was no more dock, no railroad and no ships.”

Rescue assistance was rushed from nearby towns and other military bases. The town of Port Chicago was severely damaged by the explosion. And though many suffered injuries, none of its citizens were killed.

During the night and early morning, the injured were removed to hospitals, and many of the black enlisted men were evacuated to nearby stations, mainly to Camp Shoemaker in Oakland. Others remained at Port Chicago to clear away debris and search for what could be found of bodies.

The search for bodies was grim work. One survivor recalled the experience: “I was there the next morning. We went back to the dock. Man, it was awful; that was a sight. You'd see a shoe with a foot in it, and then you'd remember how you'd joked about who was going be the first one out of the hold. You'd see a head floating across the water --just the head --or an arm.... it was just awful.”

Some 200 black enlisted men volunteered to remain at the base and help with the clean-up operation. Three days after the disaster, Captain Merrill T. Kinne, officer-in-charge of Port Chicago, issued a statement praising the black enlisted men for their behavior during the disaster. Stating that the men acquitted themselves with "great credit.

The Aftermath Four days after the Port Chicago disaster, on 21st July 1944 a Naval Court of Inquiry was convened to "inquire into the circumstances attending the explosion." The inquiry was to establish the facts of the situation, and the Court was to arrive at an opinion concerning the cause or causes of the disaster. The inquiry lasted 39 days, and some 125 witnesses were called to testify. However, only five black witnesses were called to testify None from the group that would later resist returning to work because of unsafe practices. The Court heard testimony from survivors and eyewitnesses to the explosion, other Port Chicago personnel, ordnance experts, inspectors who checked the ships before loading, and others.

The question of Captain Kinne's tonnage figures blackboard, and the competition it encouraged, came up during the proceedings. Kinne attempted to justify this as simply an extension of the Navy's procedure of competition in target practice. He procedure of competition in target practice. He contended that it did not negatively impact on safety and implied that junior officers who said it did, did not know what they were talking about.

The Court also heard testimony concerning the fueling of the vessels, possible sabotage, defects in the bombs, problems with the winches and other equipment, rough handling by the enlisted men, and organizational problems at Port Chicago.

“The specific cause of the explosion was never officially established by the Court of Inquiry.” None in a position to have actually seen what caused the explosion had lived to tell about it.

Although there was testimony before the Court about competition in loading, this was not listed by the Court (or the Judge Advocate) as in any way a cause of the explosion. (although the court saw fit to recommend that, in future, "the loading of explosives should never be a matter of competition" -- a small slap on the wrists of the officers).

The Court of Inquiry in effect cleared the officers-in- charge of any responsibility for the disaster, and in so far as any human cause was invoked, The burden of blame was laid on the shoulders of the black enlisted men who died in the explosion.

|